Back

(111) Harm Reduction Street Outreach Clinical Services: A Case Study

Saturday, April 6, 2024

9:45 AM – 1:15 PM

Has Audio

Meredith Kerr, DNP, CRNP, FNP-C

Nurse Practitioner

SPARC / Johns Hopkins University, Maryland

Presenter(s)

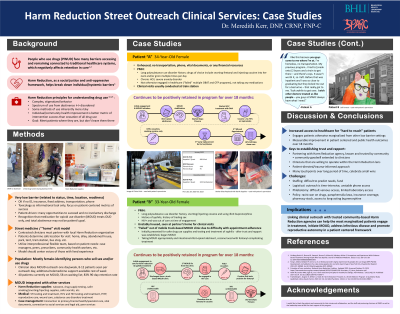

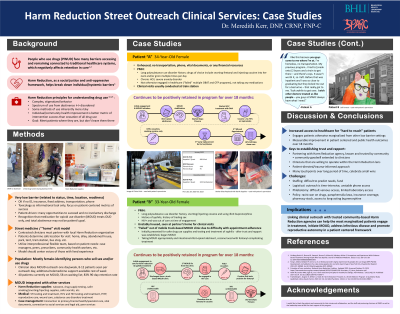

Background & Introduction: People who use drugs (PWUD) face many barriers accessing traditional healthcare modalities, and can often be hard to reach and even harder to retain in care.1,2 Clinicians can and should use the social justice and anti-oppressive framework of Harm Reduction to help break down some of these individual and systemic obstacles. Harm Reduction principles encompass an understanding that drug use is a complex, stigmatized behavior situated on a spectrum from severe disordered use to abstinence; an acknowledgement that some methods of drug use inherently carry more risk than others; and an agreement that improvement to individual and community health are better criteria for evaluating the success of interventions than is cessation of all drug use.3 Harm Reduction also includes specific risk reduction tools that are easily translatable to clinical encounters, and outreach and mobile services allow clinicians to quite literally “meet the patient where they are.”4,5 This study explores the realities of what it looks like to retain an underserved population in care through the lens of Harm Reduction, and seeks to understand the multitude of barriers that this population faces and some methods clinicians and health care systems can use to mitigate and/or overcome them.

Case Description: This case study takes place in a Mid-Atlantic urban harm reduction agency that serves female-identifying clients that sell sex and/or use drugs, and provides clinical street outreach including supplying safer drug use equipment kits and naloxone, medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and infectious disease testing and treatment through partnership with contracted clinicians. This clinical case presentation delves into the effectiveness of this modality of clinical care by following the trajectory of 2 patients over the course of a year.

The first study patient is unhoused, and does not have transportation, a phone, vital documents, or any financial resources; and clinical visits with her, including toxicology, usually take place at a public train station. The patient has a long polysubstance use disorder history, and her drugs of choice are snorting fentanyl and injecting cocaine into her neck and/or groin. She is not otherwise engaged in healthcare, and past medical history is also notable for chronic hepatitis C, and generalized anxiety disorder. She was positively retained in this program for over a year, from initial engagement in care, to successful buprenorphine initiation, subsequent opioid abstinence supported by toxicological evidence, cessation of injection drug use in favor of modes of use with less health risks, and cure of chronic hepatitis C using direct-acting antivirals.

The second study patient also has polysubstance use disorder, is HIV+ and was out of care at time of engagement in this outreach program, was snorting cocaine and using illicit buprenorphine to self-medicate an opioid use disorder, and has a history of sexually transmitted infections (STI) and illicitly trading sex. Interestingly, this patient had previously been engaged in MOUD at a mobile truck clinic, but had been discharged several months earlier as “lost to follow up” due to difficulty with appointment adherence. She initially presented for safer drug use supplies and testing and treatment of syphilis, and after trust and rapport was established over several clinical visits to her home, became interested in MOUD and HIV care and is now undetectable. She has ceased intentional illicit opioid use, though continues to snort cocaine which may be adulterated with fentanyl given the current state of the drug supply which continues to complicate her treatment. She continues to be retained in care and engaged with case management services at the agency.

Conclusion & Discussion: These are both examples of patients that would very likely not otherwise have been willing or able to access health care, including MOUD, if it were not for this Harm Reduction based outreach model. By bringing care directly to them, these patients’ objective and subjective health outcomes were greatly improved over the course of one year. Both patients had experienced many traumatic encounters with health care providers in the past and were understandably mistrustful of the healthcare industry. The keys to establishing trust and rapport included the extensive outreach work already done by the Harm Reduction agency, creating community goodwill that then extended to the partnering clinicians that were willing to operate within the Harm Reduction lens. Utilizing the risk reduction techniques under the Harm Reduction umbrella and a patient-directed and trauma-informed approach allowed clinicians to work with PWUD in ways that aren’t possible in traditional medical facilities but that yielded significant positive results. This model is not without challenges – including staffing, cost per patient, logistical complications and geographic-specific legal implications – but the benefits are hard to ignore.

References: 1. Carlberg-Racich S, Sherrod D, Swope K, Brown D, Afshar M, Salisbury-Afshar E. Perceptions and Experiences With Evidence-based Treatments Among People Who Use Opioids. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2023; 17 (2): 169-173. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001064.

2. Fong C, Mateu-Gelabert P, Ciervo C, et al. Medical provider stigma experienced by people who use drugs (MPS-PWUD): Development and validation of a scale among people who currently inject drugs in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108589. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108589

3. Principles of harm reduction. National Harm Reduction Coalition. Updated 2020. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/NHRC-PDF-Principles_Of_Harm_Reduction.pdf

4. Hawk M, Coulter RWS, Egan JE, et al. Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):70. Published 2017 Oct 24. doi:10.1186/s12954-017-0196-4

5. Frankeberger J, Gagnon K, Withers J, Hawk M. Harm Reduction Principles in a Street Medicine Program: A Qualitative Study [published online ahead of print, 2022 Oct 13]. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2022;1-17. doi:10.1007/s11013-022-09807-z

Case Description: This case study takes place in a Mid-Atlantic urban harm reduction agency that serves female-identifying clients that sell sex and/or use drugs, and provides clinical street outreach including supplying safer drug use equipment kits and naloxone, medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), and infectious disease testing and treatment through partnership with contracted clinicians. This clinical case presentation delves into the effectiveness of this modality of clinical care by following the trajectory of 2 patients over the course of a year.

The first study patient is unhoused, and does not have transportation, a phone, vital documents, or any financial resources; and clinical visits with her, including toxicology, usually take place at a public train station. The patient has a long polysubstance use disorder history, and her drugs of choice are snorting fentanyl and injecting cocaine into her neck and/or groin. She is not otherwise engaged in healthcare, and past medical history is also notable for chronic hepatitis C, and generalized anxiety disorder. She was positively retained in this program for over a year, from initial engagement in care, to successful buprenorphine initiation, subsequent opioid abstinence supported by toxicological evidence, cessation of injection drug use in favor of modes of use with less health risks, and cure of chronic hepatitis C using direct-acting antivirals.

The second study patient also has polysubstance use disorder, is HIV+ and was out of care at time of engagement in this outreach program, was snorting cocaine and using illicit buprenorphine to self-medicate an opioid use disorder, and has a history of sexually transmitted infections (STI) and illicitly trading sex. Interestingly, this patient had previously been engaged in MOUD at a mobile truck clinic, but had been discharged several months earlier as “lost to follow up” due to difficulty with appointment adherence. She initially presented for safer drug use supplies and testing and treatment of syphilis, and after trust and rapport was established over several clinical visits to her home, became interested in MOUD and HIV care and is now undetectable. She has ceased intentional illicit opioid use, though continues to snort cocaine which may be adulterated with fentanyl given the current state of the drug supply which continues to complicate her treatment. She continues to be retained in care and engaged with case management services at the agency.

Conclusion & Discussion: These are both examples of patients that would very likely not otherwise have been willing or able to access health care, including MOUD, if it were not for this Harm Reduction based outreach model. By bringing care directly to them, these patients’ objective and subjective health outcomes were greatly improved over the course of one year. Both patients had experienced many traumatic encounters with health care providers in the past and were understandably mistrustful of the healthcare industry. The keys to establishing trust and rapport included the extensive outreach work already done by the Harm Reduction agency, creating community goodwill that then extended to the partnering clinicians that were willing to operate within the Harm Reduction lens. Utilizing the risk reduction techniques under the Harm Reduction umbrella and a patient-directed and trauma-informed approach allowed clinicians to work with PWUD in ways that aren’t possible in traditional medical facilities but that yielded significant positive results. This model is not without challenges – including staffing, cost per patient, logistical complications and geographic-specific legal implications – but the benefits are hard to ignore.

References: 1. Carlberg-Racich S, Sherrod D, Swope K, Brown D, Afshar M, Salisbury-Afshar E. Perceptions and Experiences With Evidence-based Treatments Among People Who Use Opioids. Journal of Addiction Medicine. 2023; 17 (2): 169-173. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001064.

2. Fong C, Mateu-Gelabert P, Ciervo C, et al. Medical provider stigma experienced by people who use drugs (MPS-PWUD): Development and validation of a scale among people who currently inject drugs in New York City. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2021;221:108589. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108589

3. Principles of harm reduction. National Harm Reduction Coalition. Updated 2020. Accessed October 20, 2023. https://harmreduction.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/NHRC-PDF-Principles_Of_Harm_Reduction.pdf

4. Hawk M, Coulter RWS, Egan JE, et al. Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduct J. 2017;14(1):70. Published 2017 Oct 24. doi:10.1186/s12954-017-0196-4

5. Frankeberger J, Gagnon K, Withers J, Hawk M. Harm Reduction Principles in a Street Medicine Program: A Qualitative Study [published online ahead of print, 2022 Oct 13]. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2022;1-17. doi:10.1007/s11013-022-09807-z

Learning Objectives:

- describe risk reduction tools under the Harm Reduction umbrella and their applicability to providing effective, trauma-informed patient care for PWUD.

- list 3 common barriers to care for under-resourced PWUD, and associated strategies providers can implement to overcome those barriers.

- discuss benefits and limitations of the outreach/street medicine modality of providing MOUD in an urban setting.