Associations between umbilical cord drug testing results and PHQ-9 scores (Pilot Study)

(69) Associations Between Umbilical Cord Drug Testing Results and PHQ-9 Scores (Pilot Study)

Saturday, April 6, 2024

9:45 AM - 1:15 PM

Abby Davison

Medical Student

University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine, Iowa

Presenter(s)

Background & Introduction: Substance use disorder (SUD) during pregnancy can lead to poorer pregnancy outcomes, including increased maternal and infant morbidity and mortality. The CDC identified “mental health conditions (including deaths to suicide and overdose/poisoning related to substance use disorder)” to be the leading cause of pregnancy-related deaths and there is a critical need for screening, identification, and intervention for SUD in pregnancy. In the general population, other mental health disorders frequently coexist and may exacerbate SUD. Perinatal substance use is associated with co-existing mood disorders, and polysubstance use is associated with a high likelihood of perinatal depression. Screening for mental health concerns at multiple points during pregnancy/postpartum with a validated tool, such as Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), should be offered to pregnant persons establishing care. Universal screening for perinatal substance use with a validated tool, and not by biological testing such as urine screening, is recommended as well. Little is known about the association between perinatal SUD and pre/post-natal PHQ-9 scores in the antepartum and early postpartum period. This pilot study aims to determine if associations exist between maternal substance use and PHQ-9 scores as a measure of depressive symptoms, and what future study might be possible.

Methods: Umbilical cord testing for substance use in pregnancy at our academic institution is done by the newborn care team. A retrospective chart review was completed for 170 neonates and their birthing parent. The cohort included those whose umbilical cord underwent drug screening following delivery at the University of Iowa (UIHC) from January 2015 to February 2023 based on protocol listing criteria for testing—however provider discretion is allowed. Demographic data, obstetrical/neonatal outcomes, drug screening results, and other health history information from the antepartum period, delivery, and postpartum period were collected from the electronic medical record. In this study, PHQ-9 scores were used as a measure of depressive symptoms. A score > 10 is generally considered concerning for a mood disturbance, and referred to as an abnormal screen for this study. PHQ-9 scores were obtained from pregnant persons at the new obstetric visit, 28-week or another third trimester visit, postpartum while in-patient on labor and delivery, and the post-partum visit at 2 and/or 6 weeks.

All data obtained from charts was collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). Chi-square or Fischer exact tests, and t-tests were used when appropriate to analyze associations between drug screening results and PHQ-9 scores.

Results: Demographics: The cohort of pregnant persons (n=170) included people who identified as white (n=112, 65.9%), black (n=34, 20.0%), Hispanic (n=11, 6.5%), or other (including multiple races) (n=13, 7.6%). 113 pregnant persons (66.5%) had public insurance, 48 (28.2%) had private insurance, and 9 (5.2%) had some other form of insurance.

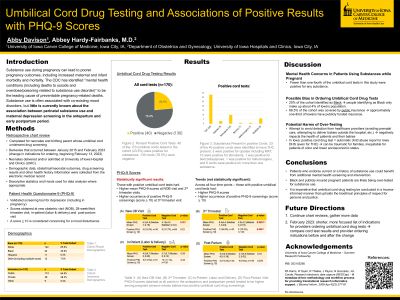

Umbilical cord drug screening results: 40 of the 170 umbilical cords tested in this cohort returned positive for substances (23.5%). 7 of those 40 positive tests (17.5%) showed legally prescribed substances, but 39 of the 40 (97.5%) showed illicit substances that were not prescribed. Of these 39 positive tests showing illicit substances, the most common substance identified was THC (n=33, 84.6%). Other substances identified included opiates (n=3), stimulants (n=10), benzodiazepines (n=1), hallucinogens (n=1), and 6 cords were positive for multiple substances.

PHQ-9 scores: Pregnant persons whose umbilical cord screened positive for substances had PHQ-9 scores that trended higher than those whose cords screened negative at all four time points (new obstetric visit, 3rd trimester visit, labor and delivery in-patient, and postpartum visit). Notably, at the new obstetric visit (n=135), pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested positive for substances had a mean PHQ-9 score of 6.2 + 4.3, while those whose cords tested negative had a mean score of 4.15 + 4 (p=0.02). At the 3rd trimester visit (n=155), pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested positive for substances had a mean PHQ-9 score of 8.4 + 6.4, while those whose cords tested negative had a mean score of 4.3 + 4.2 (p=0.0007). Additionally, at all four time points, a larger proportion of the group with positive cord drug tests had a positive PHQ-9 score (>10) than those with negative cord drug tests. Notably, at the 3rd trimester visit, 7 pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested positive for substances had a PHQ-9 score >10 (n=32, 36.8%), while 9 pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested negative for substances had a PHQ-9 score >10 (n=122, 10.3%) (p=0.008).

Conclusion & Discussion: The mean PHQ-9 scores at new obstetrical visit and in 3rd trimester in pregnancy persons, with positive cord drug tests were significantly higher than the mean PHQ-9 scores of those with negative cord tests (p=0.02 and 0.0007, respectively). At the 3rd trimester visit, pregnant persons with positive cord drug tests were significantly more likely to have a positive PHQ-9 score (>10) than those with a negative cord test (p=0.008). Due to the small sample size, we cannot draw specific conclusions about substance use during pregnancy and PHQ-9 scores. Additionally, all patients delivered at the same hospital, so it is unclear whether results would generalize to patients delivering outside of UIHC or Iowa. However, the data show a trend of higher PHQ-9 scores among those who used substances during their pregnancy. Patients who endorse current or a history of substance use may benefit from additional mental health screening and intervention. This study is on-going.

Additionally, THC was the most common substance present in umbilical cords that tested positive. Though recreational THC is illegal in Iowa, it is important to note that it is legal in surrounding states such as Illinois and Missouri.

References: 1. Cook, J. L., Green, C. R., de la Ronde, S., Dell, C. A., Graves, L., Ordean, A., Ruiter, J., Steeves, M., & Wong, S. (2017). Epidemiology and Effects of Substance Use in Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can, 39(10), 906-915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.07.005

2. Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

3. Pentecost R, Latendresse G, Smid M. (2021). Scoping Review of the Associations Between Perinatal Substance Use and Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 50(4):382-391. doi:10.1016/j.jogn.2021.02.008

4. Price HR, Collier AC, Wright TE. Screening Pregnant Women and Their Neonates for Illicit Drug Use: Consideration of the Integrated Technical, Medical, Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:961. Published 2018 Aug 28. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00961

5. Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 4. Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Jun 1;141(6):1232-1261. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005200. PMID: 37486660.

Methods: Umbilical cord testing for substance use in pregnancy at our academic institution is done by the newborn care team. A retrospective chart review was completed for 170 neonates and their birthing parent. The cohort included those whose umbilical cord underwent drug screening following delivery at the University of Iowa (UIHC) from January 2015 to February 2023 based on protocol listing criteria for testing—however provider discretion is allowed. Demographic data, obstetrical/neonatal outcomes, drug screening results, and other health history information from the antepartum period, delivery, and postpartum period were collected from the electronic medical record. In this study, PHQ-9 scores were used as a measure of depressive symptoms. A score > 10 is generally considered concerning for a mood disturbance, and referred to as an abnormal screen for this study. PHQ-9 scores were obtained from pregnant persons at the new obstetric visit, 28-week or another third trimester visit, postpartum while in-patient on labor and delivery, and the post-partum visit at 2 and/or 6 weeks.

All data obtained from charts was collected and managed using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). Chi-square or Fischer exact tests, and t-tests were used when appropriate to analyze associations between drug screening results and PHQ-9 scores.

Results: Demographics: The cohort of pregnant persons (n=170) included people who identified as white (n=112, 65.9%), black (n=34, 20.0%), Hispanic (n=11, 6.5%), or other (including multiple races) (n=13, 7.6%). 113 pregnant persons (66.5%) had public insurance, 48 (28.2%) had private insurance, and 9 (5.2%) had some other form of insurance.

Umbilical cord drug screening results: 40 of the 170 umbilical cords tested in this cohort returned positive for substances (23.5%). 7 of those 40 positive tests (17.5%) showed legally prescribed substances, but 39 of the 40 (97.5%) showed illicit substances that were not prescribed. Of these 39 positive tests showing illicit substances, the most common substance identified was THC (n=33, 84.6%). Other substances identified included opiates (n=3), stimulants (n=10), benzodiazepines (n=1), hallucinogens (n=1), and 6 cords were positive for multiple substances.

PHQ-9 scores: Pregnant persons whose umbilical cord screened positive for substances had PHQ-9 scores that trended higher than those whose cords screened negative at all four time points (new obstetric visit, 3rd trimester visit, labor and delivery in-patient, and postpartum visit). Notably, at the new obstetric visit (n=135), pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested positive for substances had a mean PHQ-9 score of 6.2 + 4.3, while those whose cords tested negative had a mean score of 4.15 + 4 (p=0.02). At the 3rd trimester visit (n=155), pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested positive for substances had a mean PHQ-9 score of 8.4 + 6.4, while those whose cords tested negative had a mean score of 4.3 + 4.2 (p=0.0007). Additionally, at all four time points, a larger proportion of the group with positive cord drug tests had a positive PHQ-9 score (>10) than those with negative cord drug tests. Notably, at the 3rd trimester visit, 7 pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested positive for substances had a PHQ-9 score >10 (n=32, 36.8%), while 9 pregnant persons whose umbilical cords tested negative for substances had a PHQ-9 score >10 (n=122, 10.3%) (p=0.008).

Conclusion & Discussion: The mean PHQ-9 scores at new obstetrical visit and in 3rd trimester in pregnancy persons, with positive cord drug tests were significantly higher than the mean PHQ-9 scores of those with negative cord tests (p=0.02 and 0.0007, respectively). At the 3rd trimester visit, pregnant persons with positive cord drug tests were significantly more likely to have a positive PHQ-9 score (>10) than those with a negative cord test (p=0.008). Due to the small sample size, we cannot draw specific conclusions about substance use during pregnancy and PHQ-9 scores. Additionally, all patients delivered at the same hospital, so it is unclear whether results would generalize to patients delivering outside of UIHC or Iowa. However, the data show a trend of higher PHQ-9 scores among those who used substances during their pregnancy. Patients who endorse current or a history of substance use may benefit from additional mental health screening and intervention. This study is on-going.

Additionally, THC was the most common substance present in umbilical cords that tested positive. Though recreational THC is illegal in Iowa, it is important to note that it is legal in surrounding states such as Illinois and Missouri.

References: 1. Cook, J. L., Green, C. R., de la Ronde, S., Dell, C. A., Graves, L., Ordean, A., Ruiter, J., Steeves, M., & Wong, S. (2017). Epidemiology and Effects of Substance Use in Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can, 39(10), 906-915. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2017.07.005

2. Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. https://doi.org/10.3928/0048-5713-20020901-06

3. Pentecost R, Latendresse G, Smid M. (2021). Scoping Review of the Associations Between Perinatal Substance Use and Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 50(4):382-391. doi:10.1016/j.jogn.2021.02.008

4. Price HR, Collier AC, Wright TE. Screening Pregnant Women and Their Neonates for Illicit Drug Use: Consideration of the Integrated Technical, Medical, Ethical, Legal, and Social Issues. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:961. Published 2018 Aug 28. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00961

5. Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 4. Obstet Gynecol. 2023 Jun 1;141(6):1232-1261. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005200. PMID: 37486660.

Learning Objectives:

- Upon completion, participants will be able to describe the relationship between umbilical cord drug testing results and PHQ-9 scores during pregnancy/post-partum.

- Upon completion, participants will be able to recognize an abnormal PHQ-9 score in the context of pregnancy.

- Upon completion, participants will be able to explain how bias in umbilical cord drug testing inequitably impacts patients of color and low socioeconomic status.