Back

(81) Methadone Take-Home Flexibilities and Mortality: Permitting vs. Non-Permitting States

Saturday, April 6, 2024

9:45 AM – 1:15 PM

Has Audio

Rebecca A. Harris, MD, MSc

Assistant Professor of Family Medicine and Community Health

University of Pennsylvania, Pennsylvania

Presenter(s)

Background & Introduction: To mitigate COVID-19 exposure risks in methadone clinics, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) issued a temporary modification of regulations in March 2020 to permit extended take-home methadone doses.[1] Responding to the first wave of the pandemic, SAMHSA issued a blanket exception that allowed opioid treatment programs (OTPs), with state concurrence, to provide up to 28 days of take-home methadone for clinically stable patients and 14 days for those who were less stable. SAMHSA is now considering proposals to permanently ease restrictions on take-home methadone doses.

This study examined the association between the policy change and fatal methadone overdoses. To control for secular trend, it compared the states that permitted OTPs to relax the restrictions on take-home doses with states that did not allow the easing of restrictions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the association between take-home doses and methadone-involved overdose deaths by whether the states concurred in the exemption for take-home doses.

Methods: Mortality data were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on-line CDC-WONDER tools.[2] I compiled monthly methadone-involved overdose deaths from January 2018 to June 2022 (54 months; 27 months before the federal policy change and 27 after), stratifying by whether the state permitted OTPs to extend methadone take-home doses. I used interrupted time series analysis to model trends in monthly overdose deaths. The method constructs a counterfactual – what the trend would look like in the absence of the policy change – which is then compared with the post-intervention actual trend. A significant difference in the slopes before and after the policy change would suggest that the policy change was associated with either an increase or decrease in methadone-related overdose deaths. I also estimated the difference in change-of-slope coefficients between the two groups of states, and the average treatment effect on the treated using the difference-in-differences method.

States permitting extended take-home doses were considered the treatment group (n=42, including DC), states not permitting (n=3) were the comparison group. States were excluded if the information on methadone take-home status was inconsistent or missing (n=5), or if the state did not have an OTP (n=1).[3,4]

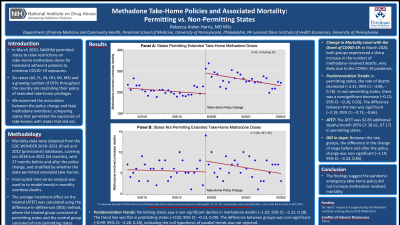

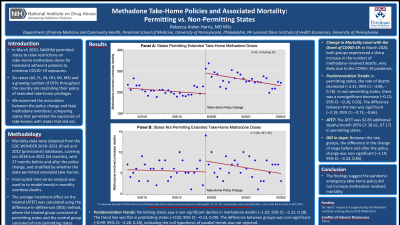

Results: Preintervention Trends: Before the policy change (January 2018 through March 2020), states permitting extended take-home doses saw a non-significant decline in methadone deaths at a rate of –1.02 per month (95% CI: –2.31, 0.28). The trend line was flat in prohibiting states at –0.02 per month (95% CI: –0.13, 0.09). The difference between groups was –0.99 (95% CI: –2.28, 0.28), indicating the null hypothesis of parallel trends was not rejected (Figure 1).

Change in Mortality Level with the Onset of COVID-19: In April 2020, both groups of states saw a sharp increase in methadone-involved deaths, estimated by subtracting the end point of the preintervention trend line (March 2020) from the start point of the postintervention trend line. In states permitting extended take-home doses, the increase was 98.02 deaths (95% CI: 65.32, 130.72), a 50.8% increase from March 2020. In states not permitting the change, the increase was 2.64 deaths (95% CI: –0.50, 5.78), a 50.6% increase.

Postintervention Trends: Following the policy change, states permitting extended take-home doses saw the rate of deaths decrease at –2.31 per month (95% CI: –3.86, –0.76). In states not extending take-home doses, there was a nonsignificant decrease in the rate of deaths post-intervention at –0.12 per month (95% CI: –0.26, 0.03). The difference between the two groups was significant at –2.19 deaths per month (95% CI: –3.73, –0.66), with states that permitted extended take-home doses showing greater reductions in monthly mortality.

Average treatment effect on the treated: The ATET estimate was 52.89 additional deaths per month (95% CI: 38.61, 67.17) in the states allowing extended doses.

Pre-Post Change in Slope: In states permitting extended doses, the rate of decrease before and after the policy change changed by –1.29 (95% CI: –3.36, 0.78), and in non-permitting states, by –0.10 (95% CI: –0.28, 0.09).

Difference-in-differences in slope: Between the two groups, the difference in the change of slope before and after the policy change was not statistically significant at –1.19 (95% CI: –3.24, 0.85).

Conclusion & Discussion: This study suggests the policy change allowing extended take-home doses did not result in an increase in monthly methadone-involved overdose deaths in states that permitted the practice. The abrupt increase in the level of methadone mortality that began in April 2020, and which occurred in both groups, was likely due to disruptions related to COVID-19. Similar increases in mortality level occurred in drug overdose deaths not involving methadone and in related domains such as alcohol-associated deaths.

This study has limitations. First, the non-permitting group of states was small limiting the ability to control for potential confounders. Second, it was unclear if methadone-related overdose deaths were due to methadone from OTPs (90% of US supply), pharmacy prescriptions for pain (9%), or other sources. Kaufman et al. report no significant link between methadone for pain and overdose rates.[5] Third, approximately 5% of death certificates did not list the drugs involved in the overdose. Fourth, this analysis examined methadone deaths in the aggregate; mortality trends may differ when disaggregated by demographic group.

These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence that the policy of extending take-home doses did not increase methadone mortality at the population level.

References: 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Methadone take-home flexibilities extension guidance. Updated March 3, 2022. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/statutes-regulations-guidelines/methadone-guidance

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the multiple cause of death files as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Methadone take-home flexibilities extension guidance. Updated December 21, 2023.

Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/statutes-regulations-guidelines/methadone-guidance

4. Roy V, Buonora M, Simon C, Dooling B, Joudrey P. Adoption of methadone take home policy by U.S. state opioid treatment authorities during COVID-19. Int J Drug Policy. 2024 Jan 5;124:104302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104302. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38183861.

5. Kaufman DE, Kennalley AL, McCall KL, Piper BJ. Examination of methadone involved overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Forensic Sci Int. 2023;344:111579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2023.111579

This study examined the association between the policy change and fatal methadone overdoses. To control for secular trend, it compared the states that permitted OTPs to relax the restrictions on take-home doses with states that did not allow the easing of restrictions. To our knowledge, this study is the first to analyze the association between take-home doses and methadone-involved overdose deaths by whether the states concurred in the exemption for take-home doses.

Methods: Mortality data were obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on-line CDC-WONDER tools.[2] I compiled monthly methadone-involved overdose deaths from January 2018 to June 2022 (54 months; 27 months before the federal policy change and 27 after), stratifying by whether the state permitted OTPs to extend methadone take-home doses. I used interrupted time series analysis to model trends in monthly overdose deaths. The method constructs a counterfactual – what the trend would look like in the absence of the policy change – which is then compared with the post-intervention actual trend. A significant difference in the slopes before and after the policy change would suggest that the policy change was associated with either an increase or decrease in methadone-related overdose deaths. I also estimated the difference in change-of-slope coefficients between the two groups of states, and the average treatment effect on the treated using the difference-in-differences method.

States permitting extended take-home doses were considered the treatment group (n=42, including DC), states not permitting (n=3) were the comparison group. States were excluded if the information on methadone take-home status was inconsistent or missing (n=5), or if the state did not have an OTP (n=1).[3,4]

Results: Preintervention Trends: Before the policy change (January 2018 through March 2020), states permitting extended take-home doses saw a non-significant decline in methadone deaths at a rate of –1.02 per month (95% CI: –2.31, 0.28). The trend line was flat in prohibiting states at –0.02 per month (95% CI: –0.13, 0.09). The difference between groups was –0.99 (95% CI: –2.28, 0.28), indicating the null hypothesis of parallel trends was not rejected (Figure 1).

Change in Mortality Level with the Onset of COVID-19: In April 2020, both groups of states saw a sharp increase in methadone-involved deaths, estimated by subtracting the end point of the preintervention trend line (March 2020) from the start point of the postintervention trend line. In states permitting extended take-home doses, the increase was 98.02 deaths (95% CI: 65.32, 130.72), a 50.8% increase from March 2020. In states not permitting the change, the increase was 2.64 deaths (95% CI: –0.50, 5.78), a 50.6% increase.

Postintervention Trends: Following the policy change, states permitting extended take-home doses saw the rate of deaths decrease at –2.31 per month (95% CI: –3.86, –0.76). In states not extending take-home doses, there was a nonsignificant decrease in the rate of deaths post-intervention at –0.12 per month (95% CI: –0.26, 0.03). The difference between the two groups was significant at –2.19 deaths per month (95% CI: –3.73, –0.66), with states that permitted extended take-home doses showing greater reductions in monthly mortality.

Average treatment effect on the treated: The ATET estimate was 52.89 additional deaths per month (95% CI: 38.61, 67.17) in the states allowing extended doses.

Pre-Post Change in Slope: In states permitting extended doses, the rate of decrease before and after the policy change changed by –1.29 (95% CI: –3.36, 0.78), and in non-permitting states, by –0.10 (95% CI: –0.28, 0.09).

Difference-in-differences in slope: Between the two groups, the difference in the change of slope before and after the policy change was not statistically significant at –1.19 (95% CI: –3.24, 0.85).

Conclusion & Discussion: This study suggests the policy change allowing extended take-home doses did not result in an increase in monthly methadone-involved overdose deaths in states that permitted the practice. The abrupt increase in the level of methadone mortality that began in April 2020, and which occurred in both groups, was likely due to disruptions related to COVID-19. Similar increases in mortality level occurred in drug overdose deaths not involving methadone and in related domains such as alcohol-associated deaths.

This study has limitations. First, the non-permitting group of states was small limiting the ability to control for potential confounders. Second, it was unclear if methadone-related overdose deaths were due to methadone from OTPs (90% of US supply), pharmacy prescriptions for pain (9%), or other sources. Kaufman et al. report no significant link between methadone for pain and overdose rates.[5] Third, approximately 5% of death certificates did not list the drugs involved in the overdose. Fourth, this analysis examined methadone deaths in the aggregate; mortality trends may differ when disaggregated by demographic group.

These findings contribute to the growing body of evidence that the policy of extending take-home doses did not increase methadone mortality at the population level.

References: 1. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Methadone take-home flexibilities extension guidance. Updated March 3, 2022. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment/statutes-regulations-guidelines/methadone-guidance

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the multiple cause of death files as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov.

3. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Methadone take-home flexibilities extension guidance. Updated December 21, 2023.

Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/medications-substance-use-disorders/statutes-regulations-guidelines/methadone-guidance

4. Roy V, Buonora M, Simon C, Dooling B, Joudrey P. Adoption of methadone take home policy by U.S. state opioid treatment authorities during COVID-19. Int J Drug Policy. 2024 Jan 5;124:104302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104302. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 38183861.

5. Kaufman DE, Kennalley AL, McCall KL, Piper BJ. Examination of methadone involved overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Forensic Sci Int. 2023;344:111579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2023.111579

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the key regulatory changes made by SAMHSA regarding take-home methadone doses during the COVID-19 pandemic and their intended purpose.

- Describe the methodology and findings of the study comparing methadone-involved overdose deaths between states permitting extended take-home doses and those that did not.

- Describe the implications of the study's results for future policies regarding methadone maintenance treatment, considering the broader context of health equity and inclusivity.